Synopses of Recent Addiction Research Provided by Dr. Mark Gold

Opioid Use Disorders and Overdoses have turned into a national health crisis, and more effective and life-saving public health responses are imperative to curb this growing epidemic. This article is the first installment in this series of four, exploring the profound role of Medication-Assisted Treatments and how to maximize their efficacy in the context of an all-encompassing treatment approach. The series explores more evidence-based, accessible and comprehensive treatment options to treat addiction, while, above all, prioritizing the saving of lives.

Role of Medicated-Assisted Treatments

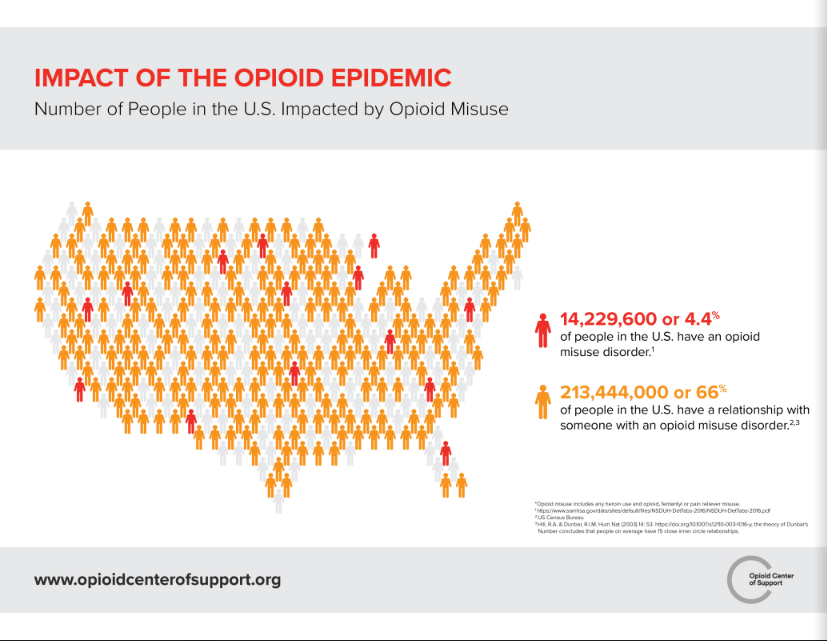

Opioid use and addiction have quickly transformed into a national health crisis of epidemic proportions and demands innovative scientific strategies and interventions. The United States is the world’s largest consumer of opioids.

The non-medicinal use of and addiction to opioids, particularly prescription pain relievers, heroin and synthetic opioids like fentanyl, has escalated into a national epidemic adversely affecting public health, social welfare, and economic progress. Every day, more than 115 people in the United States die due to overdosing on opioids.

As opioid addiction has become more and more complex, treatments have also evolved to focus on reducing deaths and harm reduction.

Medication-Assisted Treatments (MAT) utilize FDA-approved medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a “whole-patient” approach to the treatment of substance use disorders.

Treatments need to be made accessible, with more treatment providers and accurate treatment initiation at the point where the person enters the health system with an Opioid Use Disorder (OUD).

Most common MAT medications used are essentially opioids themselves, such as suboxone, methadone, and buprenorphine. Naltrexone is not. These Medication-Assisted Treatments help keep the patient’s cravings fulfilled, reduce overdose and curb the use of opioids.

Maximizing the benefits of MATs means encouraging the patient not just to take the medication, but to also participate in group and individual therapy.

It is of utmost importance that Medication-Assisted Treatments are conducted in a safe medical setting, exactly taking medications as prescribed and other psychological, medical and psychiatric services provided simultaneously.

Various studies have established that MAT can effectively reduce mortality rates among addicted patients by half or even more. Hence, all leading public health organizations acknowledge the medical worth of MATs and are often described as “the gold standard” for or the core of opioid addiction care.

Comprehensive procedural information needs to be established to create awareness among physicians regarding clinical guidelines and minimizing induction barriers. Increasing the availability of medications that can effectively treat opioid use disorder is now more crucial than ever to effectively address the epidemic of overdose deaths.

The Food and Drug Administration approves only a small number of medications for treating opioid use disorder: methadone, buprenorphine, Probuphine, suboxone, clonidine and lofexidine, and naltrexone. Roughly 20 percent of Americans who have an opioid use disorder use one of these.

Naloxone – A necessity!

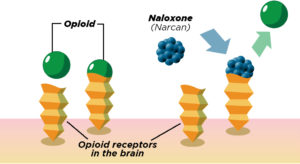

Naloxone was routinely used for overdoses in the mid-1970s, a medication designed to reverse an opioid overdose rapidly. Being an opioid antagonist, naloxone binds to opioid receptors and can reverse and stop the effects of other opioids.

In a short span of time, it can restore normal respiration to a person whose breathing slowed down or stopped altogether owing to an opioid overdose. After an overdose, a person who is not breathing can quickly come back to life. However, emergency services still need to be enlisted as the length of time that naloxone or Narcan reverses an overdose is short.

Pitt and her Stanford colleagues established that current treatments and policy proposals cannot significantly reduce deaths. US adults belonging to various stages of pain, opioid use and addiction were assessed in order to determine addiction-related deaths, life expectancy and quality-adjusted life years from 2016 to 2025 for 11 policy responses to the opioid epidemic.

Over the course of 5 years, increasing the availability of naloxone, expanding medication-assisted addiction treatment and widening psychosocial treatment was observed to heighten life years and quality-adjusted life years, and lead to a reduction in deaths. Other policies sought to limit opioid prescription supply.

This, however, lead some addicted prescription users to switch to heroin use, which ended up increasing heroin-related deaths, in the short run.

Even though some policies, in the long run, may help control addiction rates, no single policy was found capable of considerably decreasing the death rate from 5 to 10 years.

Often touted as the wonder drug, naloxone is now readily available, carried by most first responders. Its time of effect is relatively brief, even shorter than the effect of most opioids used by people. Yet, overdose deaths are at an all-time high due to the real problem not being treated.

It’s important to know that even though naloxone is an essential tool in fighting the opioid crisis, it is not a solution in itself. Patients who survive opioid overdose should be considered extraordinarily high-risk and monitored accordingly.

It is essential to have a comprehensive discussion about the resources available for overdosing patients including counseling these patients and offering them medications like buprenorphine that are used to help treat opioid use disorder directly from the ED, provide recovery coaches and create accessible treatment sites for ongoing care.

Clonidine and Lofexidine

Clonidine and Lofexidine (known as alpha2-adrenergic agonists) offer an alternative approach to detoxification and induction on to Naltrexone. The Yale group of researchers invented the use of clonidine, as the first non-addicting non-opioid treatment for opioid withdrawal or detoxification in 1978. This discovery affirmed a considerable understanding of the mechanism of opioid withdrawal.

In a placebo-controlled trial consisting of 11 addicted patients in a controlled environment, clonidine reduced independent and subjective symptoms of opiate withdrawal for 240 to 360 min. In an open pilot study assessing the impact of clonidine on longer-term opiate abstinence and symptoms, the same patients did well while taking clonidine for a week.

This data connects opiate withdrawal with an increased neuronal activity in areas such as the locus coeruleus which are regulated by both alpha-2 adrenergic and opiate receptors.

Lofexidine, a branch of clonidine, came into being by the early 1980s, but it was not until 2018 that it was approved for non-opioid treatment for opioid withdrawal.

Studies showed that clonidine and lofexidine were more effective than a placebo in managing withdrawal from heroin or methadone and were associated with higher chances of finishing treatment.

Lofexidine exerted less effect on blood pressure than clonidine and proved to have an overall better safety profile. Detoxification does not constitute an entire treatment in itself but is a necessary first step for a patient to be able to take Naltrexone or Vivitrol as mean of a MAT.

Naltrexone-Vivitrol

Naltrexone, a medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is used to treat opioid use disorders and alcohol use disorders. It comes in an oral or pill form which was used in the seventies or as an injectable which lasts for one month.

Naltrexone inhibits the euphoric and sedative effects of drugs such as heroin, morphine, and codeine. Its functionality is opposite to that of heroin, buprenorphine, and methadone. Instead of activating opioid receptors in the body that diminish cravings, naltrexone binds and blocks opioid receptors.

This blocking prevents opioids like heroin or morphine from having effects on the body and brain. Hence, if individuals treated with Naltrexone continue to inject themselves with heroin, they will not experience the usual euphoric effects of the drug and may just perceive it as a waste of money.

Naltrexone reduces opioid access to the systems that control breathing, pulse and respiration. It reduces cravings and subsequent readdiction in recovering patients. Recent research has verified that naltrexone reduces reactivity to drug-conditioned cues and inhibits craving.

Extended-release naltrexone should be part of a comprehensive management program that includes psychosocial support. The development of clonidine and naltrexone as treatment facilitators highlights how neurobiological advances can be translated into new and effective clinical approaches. The potential for abuse and diversion, a concern with buprenorphine and suboxone, is non- existent with naltrexone.

Just as with all medications used in medication-assisted treatment (MAT), naltrexone should be prescribed within a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a comprehensive care plan. Vivitrol outcomes are comparable to buprenorphine or suboxone. The differences between these Medication-Assisted Treatments are limited by detoxification success rates which are critical in Vivitrol’s success.

Methadone and Buprenorphine – Medication-Assisted Treatments and Maintenance for OUDs

Methadone is a full mu-opioid receptor agonist, mainly used as replacement therapy for addiction to heroin or other opioids. Methadone’s slow onset of action when taken orally and prevention of withdrawal symptoms from 24 to 36 hours allows it to be used as either a maintenance therapy or detoxification agent. Safe and effective, methadone has enjoyed the reputation of being safe and life-saving over 40 years.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis showed a reduction in mortality among individuals with an opioid addiction who were treated with methadone (from 36.1 per 1000 person-years among people not receiving methadone to 11.3 per 1000 person-years with methadone treatment).

Numerous studies have highlighted the effectiveness of methadone for reducing illicit opioid use, morbidity and mortality, the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, illegal activities, and improving overall functioning.

Methadone, however, is seen to maintain superior retention rates and greater protection against fentanyl use and overdoses. Of the medication treatments, methadone patients have the best 5-year outcome survival, and it is often considered the gold standard for MAT.

Methadone clinics are strictly regulated by real estate and licensing barriers. By inhibiting the availability of methadone to just designated clinics, it has further widened the effective use of Medication-Assisted Treatments. The present public health crisis could serve as the catalyst for altering this law so that methadone could be delivered both within the current methadone treatment clinic model and in primary care settings.

The ability to obtain a prescription for methadone in the course of routine primary care is especially valuable for people living in non-urban areas, in which the infrastructure required for a methadone clinic may be too expensive and disproportionate to the level of need.

Approved by the FDA for management of opioid dependence in the U.S. in 2002, buprenorphine is a partial agonist of mu-opioid receptors with a low onset and long duration of action allowing for doses over alternate days. In a major random assignment study call X-BOT, buprenorphine was equal to Vivitrol at six months.

But, both treatments had numerous dropouts and failures during the first 3 and six months of the study. Suboxone and Buprenorphine have allowed the expansion of treatment beyond methadone clinics into physician offices and general hospitals.

Evidence suggests that inducing patients too slowly may contribute to poorer retention rates. Improvements in VA and Emergency room settings have allowed protocols for starting patients quickly and building dose to the point where the majority of patients are retained.

A changing perspective

Regardless, the nation’s public health is in crisis and lives need to be saved. Greater access to evidence-based treatment is necessary. Initiation of treatment needs to be prioritized immediately after an emergency or medical visit or an overdose.

Health policies based on the improvement of mental and physical health in the addicted population do not in any way harm any other groups. A wide range of comprehensive and cohesive interventions is required for the gradual eradication of the severity of this situation.

Critics argue that MAT with suboxone, methadone, or buprenorphine is merely replacing one drug like heroin with another medicine, which itself is an opioid drug. This is on the face of it, apparently true.

Critics argue that MAT with suboxone, methadone, or buprenorphine is merely replacing one drug like heroin with another medicine, which itself is an opioid drug. This is on the face of it, apparently true.

However, as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, someone using or being physically dependent on drugs is not qualification enough to constitute as a substance use disorder: true qualification maintains that usage of drugs poses a danger and added risks.

Ultimately, an OUD or opioid addiction is a disease, and it needs the help of medications at times or for extended periods of time because of the nature of this deadly disease. Unfortunately, the associated stigma often leads with the perception that addiction is a moral failing rather than a disease.

Even now some recovery programs advocate for complete abstinence from all medications, whether antidepressants or Medication-Assisted Treatments. Yet, as the opioid epidemic is now the deadliest drug overdose crisis in the nation’s history, it has only become more important to think of more evidence-based, comprehensive and effective ways of treating addiction.

Please See

What Should We Do Now to Counter the OUD Epidemic? – Improving Existing Treatments – Article 2

References:

1. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/naloxone-tool-not-solution-opioid-crisis-2017113012800

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/80526

3. https://www.cochrane.org/CD002024/ADDICTN_clonidine-lofexidine-and-similar-medications-management-opioid-withdrawal

4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6443377

5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6388273

6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30138057

7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21838837

8. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1803982

About the Author:

Mark S. Gold, M.D. served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014. Dr. Gold was the first Faculty from the College of Medicine to be selected as a University-wide Distinguished Alumni Professor and served as the 17th University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Professor.

Mark S. Gold, M.D. served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014. Dr. Gold was the first Faculty from the College of Medicine to be selected as a University-wide Distinguished Alumni Professor and served as the 17th University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Professor.

Learn more about Mark S. Gold, MD

About the Transcript Editor:

Sana Ahmed is a journalist and social media savvy content writer with extensive research, print and on-air interview skills. She has previously worked as staff writer for a renowned rehabilitation institute, a content writer for a marketing agency, an editor for a business magazine and been an on-air news broadcaster.

Sana Ahmed is a journalist and social media savvy content writer with extensive research, print and on-air interview skills. She has previously worked as staff writer for a renowned rehabilitation institute, a content writer for a marketing agency, an editor for a business magazine and been an on-air news broadcaster.

Sana graduated with a Bachelors in Economics and Management from London School of Economics and began a career of research and writing right after. Her recent work has largely been focused upon mental health and addiction recovery.

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of addictions. These are not necessarily the views of Addiction Hope, but an effort to offer a discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Addiction Hope understand that addictions result from multiple physical, emotional, environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from an addiction, please know that there is hope for you, and seek immediate professional help.

Published on October 3, 2018

Reviewed by Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on October 3, 2018

Published on AddictionHope.com