Contributor: Mark S. Gold, M.D., Professor, Washington University School of Medicine - Department of Psychiatry

Opioid Use Disorders and Opioid Overdose Epidemics

Cries for help have been increasing since the coronavirus quarantine. EMTs have been busy with COVID 19, as have community emergency departments and general hospitals. The overdose-reversal support system (Naloxone and other MATs) that we patched together to respond to the opioid use epidemic had become broken.

Suspected overdoses nationally jumped 18 percent in March, 29 percent in April and 42 percent in May, data from ambulance teams, hospitals, and police reported July 1 by the Washington Post shows [1]. We have previously discussed [2] the disruptions to the heroin and cocaine importation and distribution networks.

They have been replaced by synthetic drugs like fentanyl and methamphetamine, manufacture in China, India, Southeast Asia, and Mexico. Being stuck at home, isolated, unable to see their counselor or go to their treatment meetings in person have created the perfect storm for a re-emergence of opioid use, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdose epidemics.

We had thought we peaked when data from the Centers for Disease Control shows a marginal decline in fatal overdoses in 2018, from 70,237 to 68,557, it also reveals that fentanyl is still the primary cause of fatal overdoses. 2018 data shows that every day, 128 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids.

At least 47,600 people died in the USA from drug overdoses involving opioids in 2017, and estimates suggest 500,000 deaths due to opioid overdoses may occur over the next five years. Synthetic opioids, fentanyl, manufactured in China, India, or Mexico are a big part of this overdose problem.

Between 2012 and 2018, the number of fentanyl-induced fatal overdoses rose dramatically, accounting for a majority of overdose deaths. As described by many experts like Rummans [3], Cicero [4], and Gold [5], the number of prescriptions written for pain increased and accumulated in the medicine cabinet only to find new users in the family and others.

In 2017, health care providers across the US wrote more than 191 million prescriptions for opioid pain medication—a rate of 58.7 prescriptions per 100 people. The prescription opioid crisis was quickly followed by a heroin use epidemic and is now a fentanyl and synthetic opioid crisis where we see more primary fentanyl use disorders [6]. This trend toward fentanyl has only increased in the COVID19 epidemic.

The unprecedented increase in opioid-related overdoses and mortality has escalated exponentially, infiltrating all segments and strata of American society while concurrently overwhelming our healthcare system and befuddling policymakers. The three waves of the current opioid crisis followed: prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids.

Now, we have a synthetic or even a primary fentanyl use epidemic. It is not likely to just go away. Drug cartels can make fentanyl all over the world at little cost. One of the key findings from the report by Pardo and colleagues is that fentanyl’s death toll doesn’t grow because of new consumers, but because it replaces less deadly opioids among individuals with OUD.

Opioid use disorder and opioid addiction continue at epidemic levels in the US and worldwide. Three million US citizens and 16 million citizens worldwide have opioid use disorder. More than 500,000 in the United States are dependent on heroin.

In a recent publication in Science [7], researchers examined drug overdose deaths and unintentional drug poisonings in the United States. They demonstrated that while drug overdoses may look like they come and go, in reality, they grow year after year.

From 1979 through 2016, they grew exponentially along a remarkably smooth trajectory. Reversing opioid overdoses with Naloxone or Narcan was a crucial part of the harm reduction strategy of the ‘70s and even more critical today.

Overdose Reversal in Hospitals, by EMTs, in the Home, and the Community

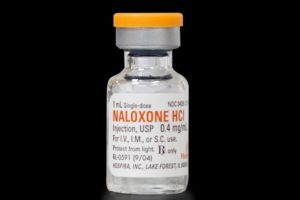

N-allyl- noroxymorphone, better known today as naloxone, is a derivative of the synthetic opioid oxymorphone. Naloxone or Narcan has been called everything from a wonder drug to the single most useful and vital intervention in reducing the impact of opioid use and overdose epidemics [8].

First patented in 1961, naloxone was approved by the FDA

in 1971 under the name Narcan. Most people refer to it by that name, Narcan. While an old medication, it is more critical today than ever before. It is the subject of a recent pharmacological review [9].

While most medications are prescribed after an office visit and examination, naloxone is most often administered by non-health professionals, EMTs, friends, and others as well are given by Emergency Room health providers in hospitals. Naloxone is safe, so safe that it is often administered when the diagnosis is in question, almost like a diagnostic test.

If the coma or low pulse low respiration crisis isn’t reversed by naloxone, then it must not be an opioid overdose the saying goes. In the emergency room, most anyone taking opioids who are having an emergency with pinpoint pupils or decreased pulse, respirations, or consciousness with a history of any new prescription opioids or illicit drug use is given Narcan.

If the coma or low pulse low respiration crisis isn’t reversed by naloxone, then it must not be an opioid overdose the saying goes. In the emergency room, most anyone taking opioids who are having an emergency with pinpoint pupils or decreased pulse, respirations, or consciousness with a history of any new prescription opioids or illicit drug use is given Narcan.

Just giving Narcan is possible, because it is very fast-acting, safe, and has remarkably few side effects. Narcan can not get a person high, and you can not tell the difference between getting an injection of naloxone intravenously and saltwater. The main side effect is the desired effect, producing acute withdrawal from opioids.

Naloxone has been in use in the United States for more than 50 years. It is the go-to or a mainstay in medical settings for reversing opioid effects, opioid toxicity, and overdose.

I gave it during my internship in the Yale Emergency Room in the ‘70s. At that time, naloxone was approved only for intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), and subcutaneous (SQ) administration. Narcan has saved and treated tens of thousands of opioid overdoses. Rescuing, resuscitating, and reviving overdose victims are critical steps in helping people with opioid use disorders(OUD).

When Pitt [10] and her colleagues at Stanford looked at what would make the most impact in reducing OUD deaths, it was Narcan. No other prevention or treatment or public health intervention was close to as effective. Prescribing naloxone to opioid users and encouraging those patients with an OUD to have Narcan with them, while providing MATs and appropriate counseling, is the essence of the harm reduction component of a comprehensive treatment model for OUD.

Not only OUD patients, non-prescription opioid users, pain patients given Narcan prescriptions, older patients, and others should be counseled regarding the signs and symptoms of opioid overdose, including pinpoint pupils, shallow or absent breathing, and unresponsiveness. If an overdose is suspected, naloxone should be administered by anyone who has it, as soon as possible. Then, call 911.

Naloxone - Pharmacology

Pharmacologically, naloxone is a high-affinity competitive antagonist at the μ-,κ-, and δ-opioid receptors. Naloxone is considered a “pure” antagonist. Naloxone, which effectively displaces any full and/or partial agonists (e.g., heroin, oxycontin, fentanyl) occupying opioid receptors which produce euphoria, sedation, sleepiness, respiratory depression, bradycardia, analgesia, and small pupils. Thus, naloxone is a real wonder drug- fast-acting, safe, easily administered opioid antidote, capable of reversing both opioid intoxication states and overdose.

More recently, an intranasal (IN) formulation of naloxone was invented and brought to market. IN delivery reduced the need for IV access (it can be challenging to find a vein in OUD overdose or in people who inject drugs) during emergencies, needlestick injuries or disposal issues, and made the medication available to most everyone.

All of a sudden, medically untrained individuals could safely administer naloxone with a reasonable probability of reversing the opioid-induced overdose and respiratory depression. Intranasal (IN ) naloxone was similar in safety, rescue, and overdose reversal efficacy to iv Narcan. Narcan Nasal Spray made it possible for friends, lay first responders, family, and others to use Narcan to save a life.

The onset of action varies depending on the route of administration but can be as fast as one minute when delivered. When administered IV, naloxone usually fully reverses the opioid effects within a few minutes. In patients who present short of breath with blue color, especially at home or outside of the hospital, you should not hesitate to give larger initial doses, such as 0.4 mg to 2 mg IV or 2mg intranasal, IM, or SQ.

Initially, one spray is administered, which provides 4 mg of naloxone. Clinicians can administer subsequent doses until reaching the desired effect. Immediately following the administration of the first NAS, one should call 911 to seek emergency medical assistance. It can be dangerous to assume the patient is fine, even if they wake up and say that they are fine.

Some opioids last longer than Narcan and can come back to occupy the opioid receptors once the naloxone wears off. Cases, where the person is rescued and leaves the Emergency Room against advice only to die on the way home, have been reported.

If the patient relapses and the respiration rate decreases before emergency medical personnel arrive, administer the second dose. If repeat dosing is necessary, then it should be delivered in alternate nostrils every two to three minutes.

If the patient fails to respond to additional doses, then one must be prepared to perform other resuscitative maneuvers, including CPR. Naloxone is not a treatment for OUD but can be a critical first step in the treatment process if intervention and treatment following an overdose reversal are quickly initiated.

Overdose Reversal and then Treat the OUD

The impact of the OUD crisis has been so widespread that most Americans know someone who has overdosed, addicted, and been treated for an OUD. The effect is overwhelming and confirmed by the unprecedented three years of declining life expectancy in the United States. This decline in life expectancy is attributed to deaths of despair, depression-suicide, alcohol and drug abuse, opioid, and cocaine overdoses, and the natural progression of substance use disorders. [11]

The impact of the OUD crisis has been so widespread that most Americans know someone who has overdosed, addicted, and been treated for an OUD. The effect is overwhelming and confirmed by the unprecedented three years of declining life expectancy in the United States. This decline in life expectancy is attributed to deaths of despair, depression-suicide, alcohol and drug abuse, opioid, and cocaine overdoses, and the natural progression of substance use disorders. [11]

Ensuring ready access to naloxone is one of SAMHSA’s Five Strategies to Prevent Overdose Deaths. Co-prescribing of naloxone with high dose opioid prescriptions and the creation of standing orders allows dispensing to naloxone by pharmacists to patients at-risk.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have implemented legislation to increase access to naloxone by allowing distribution by pharmacists, simplifying the process of obtaining naloxone, and expanding distribution to friends and families of individuals at risk for overdose. In 46 states, Good Samaritan laws have been implemented that protect bystanders and individuals from arrest or prosecution for administering naloxone in good faith.

As a result, the number of naloxone prescriptions dispensed by retail pharmacies increased by 106% from 2017 to 2018. The lowest percent of naloxone prescriptions from retail pharmacies occurred primarily in rural counties—areas that have been especially devastated by the opioid crisis [12].

While not a treatment per se for OUD, a harm reduction method for minimizing the risk of overdose is take-home naloxone. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist used to reverse an opioid overdose, and take-home naloxone programs aim to prevent fatal overdose.

We know that nearly all opioid overdoses can be reversed by naloxone and that OUD can be successfully treated with evidence-based, patient-centered treatments of adequate duration and intensity. The use of the overdose as a teachable moment, supplemented by peer and professional interventionists, can promote the transition from near-death and overdose to buprenorphine or methadone treatment.

After a nonfatal overdose, connecting individuals to a treatment facility that includes MAT is essential to positive outcomes [13]. Yet, making this hand-off is difficult and often fails.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic, relapsing disease. OUD is associated with legal, interpersonal, health, and employment problems. Medications have been demonstrated to be safe and effective for OUD and approved by the FDA.

These medications are: methadone (a full opioid agonist), buprenorphine (a partial agonist), and naltrexone (an opioid antagonist) [14]. MATs are safe and effective, reducing overdose in those patients who are treatment adherent. Unfortunately, approximately 50% or more patients drop out of treatment prematurely.

Longer duration of therapy has the best outcomes [15]. But, treatment is slow and relapses common. Treatments for OUD are limited by poor adherence to treatment recommendations. Discontinuation of MAT is associated with high rates of relapse and an increased risk of overdose. People with OUD, whether in or out of surgery but especially after leaving treatment, should be carrying Narcan.

Recent data suggest that overdose risk continues long after patients complete treatment with buprenorphine [16]. The availability of naloxone largely determines overdose reversal at the place and the time that overdose occurs.

Opioid overdose reversal is similar to acute allergy anaphylaxis reversal with epinephrine. You need the epi-pen just like you need the naloxone and the willingness to administer naloxone [17]. Yet we cannot know, with any degree of certainty,

Summary: Naloxone - Narcan

With EMTs, general hospitals, and emergency departments overwhelmed, and without reliable face-to-face access to addiction evaluations and treatments, the opioid overdose response system needs a reinforced and Narcan armed and trained citizen and family base. Naloxone (Narcan) is a non-opioid wonder drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

With EMTs, general hospitals, and emergency departments overwhelmed, and without reliable face-to-face access to addiction evaluations and treatments, the opioid overdose response system needs a reinforced and Narcan armed and trained citizen and family base. Naloxone (Narcan) is a non-opioid wonder drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

It is impossible to know where or when a potentially fatal opioid overdose will occur. But, improving Narcan availability is the best chance of saving lives from overdose. It is short-acting, and by temporarily reversing the effects of opioids, it gives a person with an opioid use disorder (OUD) a second chance—and opportunity to receive treatment.

The federal government has now recommended that the drug be readily available as an over-the-counter formula in most pharmacies. Naloxone is available without a prescription in 43 states. Besides being available in hospitals, the drug is carried by emergency medical staff as well as law enforcement personnel.

Also, the availability of naloxone over the counter has made it easier for family members and caregivers of patients with opioid use disorder to administer the drug. It is evident, logical, and well-reasoned to increase naloxone availability in emergency departments, ambulances, and among emergency medical technicians (EMTs), as they routinely encounter opioid overdose.

However, improving naloxone access at other points of care where overdose risk is likely, remains a challenge. An excellent place to start is by encouraging all patients with OUD to carry naloxone, for their loved ones to carry naloxone, and for their homes to have naloxone nearby in the bedroom or bathroom.

Current and past OUD patients, as well as their loved ones, are a high risk of overdose group and should have naloxone nearby at all times. Naloxone can reverse an opioid overdose, but it should be thought about like cardioversion or CPR rather than a treatment for an underlying disease.

There is no evidence even to suggest that having an overdose and rescue changes the course of an OUD or substance use disorder. So, while Narcan saves lives and is a wonder drug, it does not replace an intervention, treatment with a MAT, a counselor, a good treatment program, and a treatment plan.

References:

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/07/01/coronavirus-drug-overdose/

[2] https://www.addictionpolicy.org/post/copy-of-what-people-with-a-substance-use-disorder-need-to-know-about-covid-19

[3] Rummans TA, Burton MC, Dawson NL. How Good Intentions Contributed to Bad Outcomes: The Opioid Crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(3):344-350. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.020

[4] Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1295-1296. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1601875

[5] Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid-Use Disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-2086. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.029

[6] https://www.addictionpolicy.org/post/the-fentanyl-crisis-is-only-getting-worse

[7] Jalal H, Buchanich JM, Roberts MS, et al. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science. 2018;361(6408). pii: eaau1184. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1184.

[8] Srivastava AB, Gold MS. Naltrexone: A History and Future Directions. Cerebrum. 2018;2018:cer-13-18. Published 2018 Sep 1.

[9] Jordan MR, Morrisonponce D. Naloxone. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

[10] Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the US opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

[11] Koh HK, Parekh AH, Park JJ. Confronting the rise and fall of US life expectancy. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1963-1965; Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA. 2018;1(2):e180217.

[12] Guy GP, Haegerich TM, Evans ME, Losby JL, Young R, Jones CM. Vital signs: pharmacy-based naloxone dispensing – United States, 2012-2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:679-686.

[13] Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. Published 2020 Feb 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

[14] Bell J, Strang J. Medication Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87(1):82-88. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.020

[15] Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid-Use Disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-2086. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.029

[16] Oesterle TS, Thusius NJ, Rummans TA, Gold MS. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid-use disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(10):2072-2086.; Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, et al. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35(1):22-35.; Williams AR, Samples H, Crystal S, Olfson M. Acute care, prescription opioid use, and overdose following discontinuation of long-term buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2019; Dec 2:appiajp201919060612.

[17] Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the US opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

About the Author:

Mark S. Gold, M.D., Professor, Washington University School of Medicine - Department of Psychiatry, served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014.

Mark S. Gold, M.D., Professor, Washington University School of Medicine - Department of Psychiatry, served as Professor, the Donald Dizney Eminent Scholar, Distinguished Professor and Chair of Psychiatry from 1990-2014.

Dr. Gold was the first Faculty from the College of Medicine to be selected as a University-wide Distinguished Alumni Professor and served as the 17th University of Florida’s Distinguished Alumni Professor.

Learn more about Mark S. Gold, MD

The opinions and views of our guest contributors are shared to provide a broad perspective of addictions. These are not necessarily the views of Addiction Hope, but an effort to offer a discussion of various issues by different concerned individuals.

We at Addiction Hope understand that addictions result from multiple physical, emotional, environmental and genetic factors. If you or a loved one are suffering from an addiction, please know that there is hope for you, and seek immediate professional help.

Published on July 7, 2020

Reviewed by Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC on July 7, 2020

Published on AddictionHope.com